Reducing the debt, part 1: the politics

Last week I proposed a 10-word Democratic agenda for financial freedom:

Treat cost disease, reduce the debt, and save Social Security.

Cost disease is when prices in a sector go up faster than overall wages, year over year. Housing and healthcare are most afflicted. You can read my Substack and Economist essays about how to treat cost disease for the middle class.

This newsletter moves on to reducing the debt – the politics. (Next time, the policies.)

The president's just-passed tax-and-Medicaid cuts will explode the debt. They will add $4 trillion to the debt by 2034. The United States government will spend more on interest than on the military. Or Medicare. Meanwhile, the tax code has become more complicated and less fair.

Democrats voted unanimously against this fiscal recklessness. Ballooning debt is a tax on the next generation. It will be paid by millennials and Gen Z through higher taxes & inflation, reduced services, and less emergency readiness.

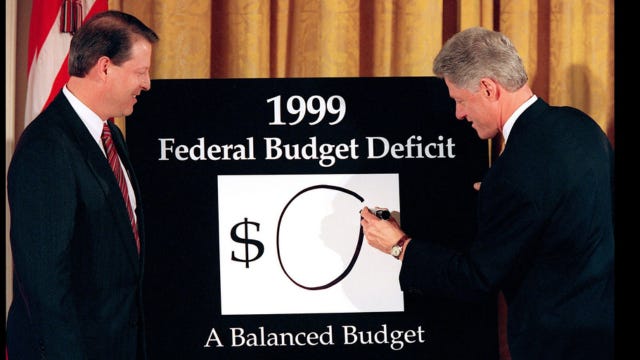

The last president to get control of the debt was a Democrat (Bill Clinton). The next president to do so will be, too. Given how MAGA just mauled the tax code, it’s clear Republicans are no longer the party of fiscal responsibility.

Paul J. Richards—AFP/Getty Images

Suppose it’s January 2029 and the trifecta in Washington has flipped: a Democrat has just been sworn in as president and they are working with slim majorities in both the House and Senate. Here’s one presidential approach to the politics of debt reduction:

First, declare the objective: debt below 100% of gross domestic product by 2040 (“100 by 40”). Economists will hail that as prudent. The Treasuries market will consider it credible.

Next, chart two competing courses to the objective.

By Executive Order, charter a bipartisan Commission on Debt Reduction. The bipartisan Commission would be appointed by the president and by both the majority and minority leaders of the House and the Senate. Its mandate would be to hit the 100 by 40 objective through tax, spending, and pro-growth reforms.

Simultaneously, begin the legislative process for budget reconciliation. Reconciliation is the congressional process by which simple majorities in both the House and Senate can pass tax and spending legislation. It bypasses the 60-vote filibuster threshold in the Senate. It is a party-line mechanism of action. Issue a statement with the Speaker and Senate Majority Leader that this reconciliation will have the same mandate as the Commission: hit the 100 by 40 objective through tax, spending, and pro-growth reforms.

With these two initiatives underway, call the House and Senate Republicans leaders. Issue a threat and offer a deal.

The threat: Democrats will ram a tax-and-spending bill through Congress. It’s a credible threat; both Joe Biden and Donald Trump did it by the midpoint of their first year in office.

Then, the deal: work with the majority to pass enabling legislation for this Commission on Debt Reduction. The legislation would decree that the final package approved by the Commission must be brought up in its entirety for an up-or-down vote in both chambers, no amendments. It would also decree that, should the Commission’s package be passed into law, then no budget reconciliation is in order for the remainder of the congressional term.

Republican leadership would be hard-pressed to refuse this offer. From a policy perspective, they would loathe what’s otherwise coming down the pike from Democratic party-line legislation. Politically, their base would punish them for not working to neutralize it. Swing voters would also disapprove of a new president’s olive branch being snapped by the minority.

Should this political gambit succeed, Washington would have two swings at fiscal responsibility. First, the bipartisan Commission’s package would get an up-or-down vote. In the honeymoon period of their term, the president could be expected to deliver nearly the full Democratic caucus in the House and Senate.

A small but vocal number of Democrats would refuse, though. They would object to some of the bipartisan measures and insist on holding out for the party-line reconciliation. To overcome this in the House, and to pass the 60-vote filibuster threshold in the Senate, a small band of Republicans would need to get to yes via both policy merits and the Sword of Damocles of impending reconciliation.

If the bipartisan Commission’s package does fail in Congress, that reconciliation measure would then ripen. After log-rolling within the party under tight margins, I do not expect this measure would ultimately be able to fully accomplish the 100 by 40 objective, though it could still make progress. No party by itself – even pressed by a president – can digest the political pain of fiscal reform. (The same is true of immigration reform.)

What policies might a bipartisan Commission on Debt Reduction recommend to Congress? You can look at the last attempt 15 years ago, review 13 major tax and spending reforms from the Penn Wharton Budget Model, or build your own with the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

In part 2 of reducing the debt, I’ll highlight the policy themes that emerge from these & other efforts.

Oh, no! Please, anything but the dread bipartisan commission on debt reduction!!!! I was about to point out the dismal history of similar attempts but it appears that you are aware of the history. And yet you propose yet another commission. What in the world makes you think this one will work any better? Committees and commissions are simply tools by which politicians kick difficult cans down the road, or at best create a villain at whom the committee creator can point fingers/hide behind. This one, if it is ever formed, will do the same.

What is needed is an actual plan to attack the problems you describe, pitched to voters, and approved in an election. It's not that nobody knows what steps need to or should be taken. It's that nobody in either party has the guts or will to do it.

These are not opinions, they are facts, borne out over decades. Anybody who campaigns on "forming a commission" as an answer to fixing the debt will lose my vote. Period.

Ready for you to be a loud (or even the loud) voice of the Dems! Somebody needs to forthwith. And these Simple-but-not-Easys are a road map that should be seen by more than those of us following along on your Substack.